Story highlights

Nepali-speaking Gorkhas are demanding a state within India

Three people have been killed and up to 60 injured

Region-wide strike has left tourism and tea industries in ruins

The sleepy hills of India’s northeast have erupted into violence, as calls for a separate state for the area’s Nepali-speaking Gorkhas gain traction.

The protest movement – now entering into its ninth day and showing no signs of resolution – is centered around the tea producing region of Darjeeling, in West Bengal, home to the country’s largest concentration of ethnic Gorkhas.

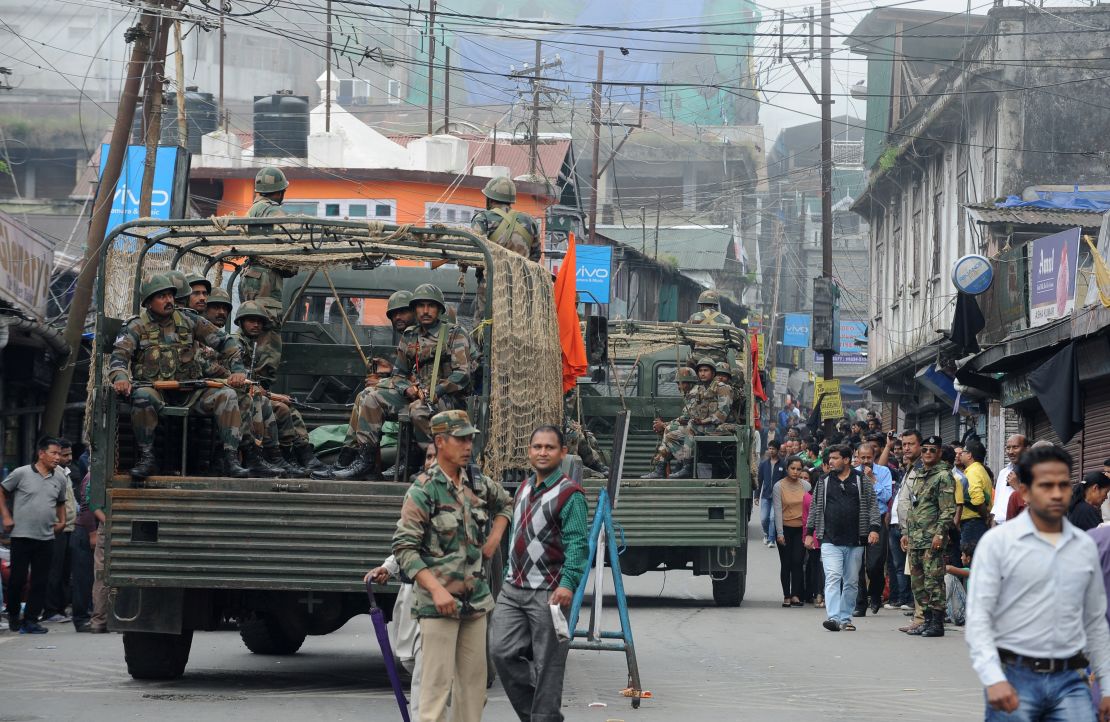

As many as three people have been killed and up to 60 injured, in ongoing clashes between protestors and local paramilitary forces. Earlier this week, military troops were drafted into the region in a bid to help quell tensions, which have hurt the region’s tea and tourist industries.

The protests are part of a wider regional strike as called for by the Gorkha Janamukti Morcha (GJM) – an ethno-nationalist political party spearheading the statehood movement – that has seen the local economy paralyzed, as workers abandon their posts and take to the streets in their thousands.

Crisis deepens

Darjeeling, a popular tourist destination in India, is best known for its sprawling tea gardens, lush green hills and panoramic views of snow-clad mountain ranges. Hundreds of Indian and foreign tourists have fled the area since the unrest began.

Who are the Indian Gorkhas?

On Friday protestors offered a 12-hour window for more than 7,000 boarding school students to safely evacuate the hills – home to some of the best boarding schools in India. Father Divya Annandam, Vice Principal at St Josephs School, told CNN some school dormitories are already facing food shortages.

The crisis started in mid-May when the government of West Bengal, the Eastern Indian state of which Darjeeling is a part, made Bengali language courses compulsory in schools across the state.

The government’s decision was viewed with hostility among the area’s Nepali-speaking community.

“We are very different from the rest of the state of West Bengal. Our language, our tradition, our culture, our heritage, our geographical condition, it doesn’t match with rest of the state, with the whole other population of West Bengal,” Roshan Giri, Secretary General of GJM told CNN.

“For Gujratis, they have Gujrat, for Biharis, they have Bihar, for Punjabis, they have Punjab…why not Gorkhaland for Gorkhas?” Giri questioned.

Gorkhaland demands

But what started as an agitation against a change in the school curriculum quickly escalated into a revival of a century-old demand for a separate state for the Indian Gorkhas, the original inhabitants of the area.

Activists claim as many as three protestors died in “indiscriminate police firing” on Gorkhaland supporters on Saturday, a claim that the police have denied.

Indian Home Minister Rajnath Singh on Sunday appealed “to the people living in Darjeeling and nearby areas to remain calm and peaceful.” He urged the protestors to not resort to violence and resolve the issue through mutual dialogue.

But outraged Gorkhaland proponents have vowed to not to give up.

“This is our final push…and we are resolved to fight until our demand is met,” said Giri.

“The West Bengal government is trying to crush our democratic movement by using police … Gorkhaland is a legitimate demand within the framework of the Indian constitution,” Giri added.

The state government’s calls for talks this week were refused by GJM officials, who have said they will now only enter into dialogue with the Indian Central Government in Delhi.

Tea industry

The indefinite strike and the government clampdown has left tourism and the tea industry – the backbone of the local economy – in tatters.

“Darjeeling’s tea industry has suffered a direct loss of more than $18 million already due to the current unrest,” Kaushik Basu, Secretary General of Darjeeling Tea Association told CNN.

Basu estimated a revenue loss of $55 million for the local tea production if the strike prolongs.

This is the peak of tourist season in Darjeeling, also known as ‘Queen of the Hills.’

Thousands of tourists would normally flock to Darjeeling around this time of the year. But local tour operators said there is not a single tourist in sight.

“The hills are virtually empty,” Summit Periwal, a local tour operator told CNN.

CNN’s Karma Dolma Gurung contributed to this report