IN BRIEF

New research using the Cassini orbiter has shown that one of Titan’s largest seas, Ligeia Mare, is composed of pure methane and not ethane, as was previously thought. And it is a terribly rich sea.

EXPLORING THE STRANGE SEAS OF TITAN

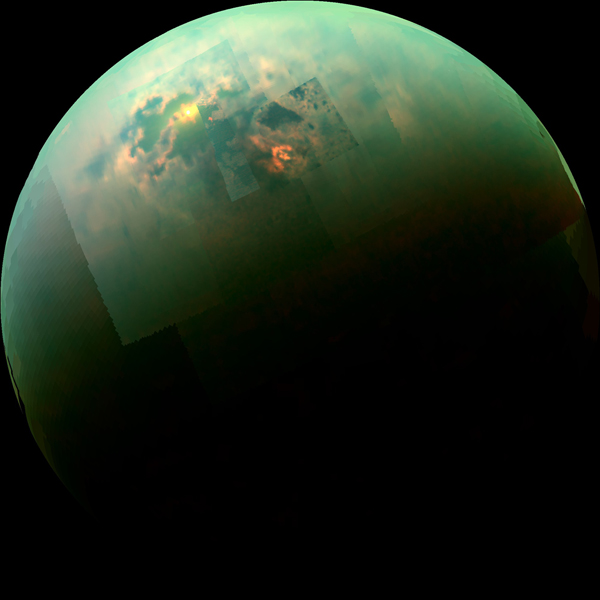

Titan’s a weird moon. Scientists have known this for some time, ever since the Voyager series of probes returned images of an enigmatic, planet-sized world shrouded in an impenetrable orange fog of organics.

But the NASA/ESA Cassini-Huygens mission has changed all that. Little by little, the layers of Titan’s mysteries have been peeled back—and the information they revealed does not disappoint.

Titan’s atmosphere is about 95% nitrogen, with the rest comprising complex hydrocarbons floating in suspension; it has lakes and seas too, which cover about 1.6 million square km (620,000 square mi) of the moon’s surface—roughly 2% of Titan’s total surface area. Most of these liquid bodies are concentrated in the northern hemisphere, with three large seas clustered near the north pole

Only a single large lake exists in the southern hemisphere.

It was thought that these seas were largely composed of ethane, which is copiously produced through photodissociation of methane in Titan’s atmosphere, and precipitates thence to rain down onto the moon’s surface—kind of a hydrocarbonic analogue to our terrestrial “hydrologic cycle.”

But Titan, apparently, still has a few surprises left in store for us.

PLUMBING THE DEPTHS

In a new study published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, a team has confirmed that Ligeia Mare—Titan’s second-largest sea, about the size of Lakes Huron and Michigan combined—is composed almost entirely of pure liquid methane.

The data for the study was collected by Cassini’s radar imager, which can penetrate the moon’s thick photochemical smog, from 2007 to 2015.

It’s not currently clear why the sea should be so unexpectedly methane-rich. “Either Ligeia Mare is replenished by fresh methane rainfall, or something is removing ethane from it,” speculates Alice Le Gall, lead author of the study.

“It is possible that the ethane ends up in the undersea crust, or that it somehow flows into the adjacent sea, Kraken Mare, but that will require further investigation.”

Indeed it will. Already, the team’s conducted some pretty sophisticated oceanographic surveys of Ligeia Mare—in an extraterrestrial first, the team used the radar instrument to sound the methane ocean’s seafloor and determine its depth. They were startled to learn that Ligeia Mare can reach depths of 160 m (525 ft) at its deepest; moreover, they found that the seabed is composed of a rich sludge of organic compounds.

It’s thought that organics, formed from the reaction of methane and nitrogen, precipitate from Titan’s atmosphere and flow into its seas, where they dissolve in the liquid methane and sink to the bottom. Further studies indicated that there’s even something like hydrocarbon “wetlands” along Ligeia Mare’s shoreline.

“It’s a marvelous feat of exploration that we’re doing extraterrestrial oceanography on an alien moon,” beams Steve Wall, deputy lead of the radar instrument team for the Cassini orbiter.

I, for one, can’t wait to see what else they’ll turn up on this weird moon.