Do We Believe Women Yet? The Battle to End Sexual Harassment

The phrase most commonly used to describe a particularly noxious form of workplace aggression is sexual harassment. But sexual predation is more apt in many instances. What is it if not predatory when a male boss abuses his power to demand physical gratification from a female employee?

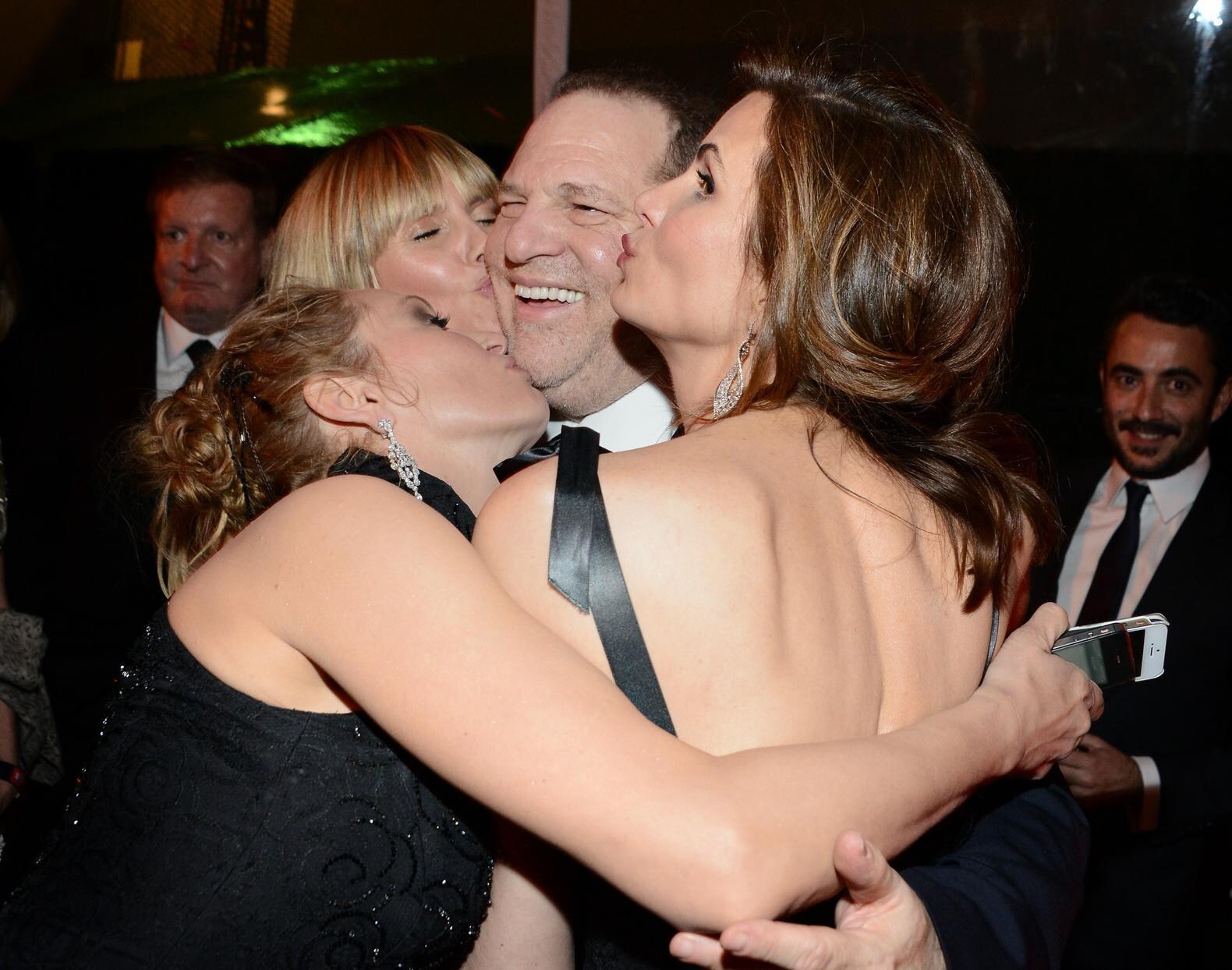

The problem is age-old. But as is obvious to anyone reading or watching the news, concerns have intensified lately with allegations of serial predation by the moviemaker Harvey Weinstein. He joins a parade of celebrities and business powerhouses accused of treating women as mere pleasure providers: Bill Cosby, Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly, Uber and Amazon Studios employees, swaths of Silicon Valley — a quorum of indecency. Not to mention that a man who boasted of grabbing women by the genitalia sits in the White House.

Not to mention that a man who boasted of grabbing women by the genitalia sits in the White House

You have to go back to the mid-1970s, when a writer named Lin Farley was teaching a course on “Women and Work” at Cornell. “I kept thinking we’ve got to come up with a name,” she recalled, “and the best I could come up with was sexual harassment of women on the job.” The phrase stuck.

New laws and workplace regulations came to pass in the hope of addressing the problem. Nevertheless, it persisted.

Day-to-day lives

Fast forward to 1991. That was when the lawyer and academician Anita Hill testified before an all-male — and strikingly unsympathetic — Senate committee that was holding hearings on the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the U.S. Supreme Court. Hill described having been sexually harassed by Thomas when he was her superior at two federal agencies, the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. He denied the accusations, and ascended to the court. Yet Hill struck a chord that still reverberates.

“One of things about my testimony, I believe, that resonated so much with women was that it seemed so regular, so much like what was going on in their day-to-day lives,” she told Retro Report.

A quarter of a century later, the Fox News anchor Gretchen Carlson became a new symbol of the issue when she sued the network’s chairman, Ailes. It was as if nothing had changed through the years. Carlson said Ailes, who died in May, had demanded she have sex with him. Like Thomas, he denied the charges. But the network’s parent company, Twenty-First Century Fox, settled the matter by paying her a reported $20 million. More women at Fox News then stepped forward with allegations of a corporate climate of sexual aggression.

Victims are more likely to be lower-paid workers whose plight rarely makes headlines

“I never ever expected to be the face of sexual harassment,” Carlson said. But she is.

She is also aware that sexual hostility on the job falls most heavily on women who are far less privileged than she or than many of the women in movies, television, high tech and other glamorous industries who also report being hounded by predatory bosses. Victims are more likely to be lower-paid workers whose plight rarely makes headlines: waitresses and female bartenders who have to fend off employers and customers with hyperactive hands, or women just trying to get through the day unscathed in the male-dominated construction industry.

More than 12,000 allegations

The Equal Opportunity Employment Commission — Thomas’ old workplace — reports receiving more than 12,000 allegations of sex-based harassment each year, with women accounting for about 83 percent of the complainants. That figure is believed to be but the tip of the iceberg. In a study issued last year, the co-chairwomen of a commission task force said that roughly three of four people experiencing such harassment never tell anyone in authority about it. Typically, they said, what women do is “avoid the harasser, deny or downplay the gravity of the situation, or attempt to ignore, forget or endure the behavior.”

Think about the vulnerability of a single mother holding down a minimum-wage job or working two jobs, Carlson told Vanity Fair last month. “There’s no way in hell she can try and come forward,” she said.

Even when women do try to speak up, they can effectively be silenced. Some may receive fat settlements, as Carlson did, but routinely they are forced into nondisclosure agreements that keep them from discussing the details of what happened. Weinstein is reported to have a history of insisting on those sorts of arrangements. If one accepts that sunlight is the best disinfectant, as an old saying goes, then pathogens inevitably abound in this atmosphere of secrecy.

Even when women do try to speak up, they can effectively be silenced

“We really aren’t helping push society forward because nobody’s hearing about these cases,” Carlson said. She added, “So many times — well, almost all times — society does not find out how prevalent sexual harassment is in the workplace.”

One remedy suggested by some advocates is to stretch the bounds of so-called “sunshine in litigation” laws that several states have enacted. Applied to tort cases in general, they essentially nullify the confidentiality clauses of legal settlements if the result is to hide conditions that qualify as “public hazards.” Some advocates argue that a workplace pattern of sexual harassment deserves to be called such a hazard, but this approach has yet to be tested in the courts.

Leading role

There seems scant reason to expect the Trump administration to play a leading role in tackling the problem. After the Fox News scandal broke in the summer of 2016, around the time Donald Trump accepted the Republican nomination for president, he was asked by a USA Today columnist what he thought should happen if his daughter Ivanka were to fall victim to similar treatment. Trump did not call for rooting out the harassers. Instead, he said, “I would like to think she would find another career or find another company if that was the case.”

Half a century ago, the makers of Virginia Slims cigarettes pitched their product to women with a slogan that spoke of new empowerment: “You’ve come a long way, baby.” At all too many workplaces, they’ve come a long way, maybe.