|

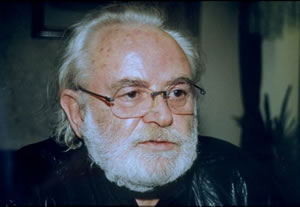

De Oostenrijkse schrijver Ernst Hinterberger werd geboren op 17 oktober 1931 in Wenen. Zie ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2008 en ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2009.xml:namespace prefix = o ns = "urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:office" />

Uit: Kaisermühlen Blues

Gitti Schimek wachte auf und spürte sofort, daß sie den Blues hatte. Das war ein schlaffer Zustand zwischen Wachen und Schlafen, nichts freute einen, und eine Wolke von Melancholie lag über allem. Erinnerungen kamen und gingen, und meist waren es keine guten. Nichts freute einen richtig, Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft verschwammen zu einem graublauen Brei, man hätte am liebsten die Augen nicht aufgemacht. Das war eben der Blues.

Der trostlose, viel zu kühle Septembersonntag war völlig verregnet. Über der Gegend zwischen Donaustrom, Entlastungsgerinne und Alter Donau lag undurchdringlicher Nebel. Vom knatternd kreisenden und rot blinkenden Polizeihubschrauber schaute der Bezirksteil Kaisermühlen wahrscheinlich aus, als würde er zwischen den Gewässern versinken.

Aber die paar Straßen und Gassen, aus denen Kaisermühlen bestand, waren nicht versunken, sondern von Leben erfüllt. Es zeigte sich zwar wegen des miesen Wetters kaum wer auf der Straße, aber zwischen den vier Wänden ihrer Wohnungen lebten massenhaft Leute.

Lebten, starben, wurden durch andere Menschen ersetzt. Es bestand nicht die geringste Gefahr, daß Kaisermühlen ausstarb.

Kaisermühlen ...

Bis vor etwa hundertzwanzig Jahren hatte es hier, wo jetzt Straßen, Gassen und Gemeindebauten waren, nichts als das Wasser der unregulierten Donau und mehrere Schiffsmühlen gegeben.

Aber dann war die moderne Zeit gekommen. Die Donau war reguliert worden, und man hatte die seit zweihundert Jahren in Betrieb stehenden Mühlen mangels fließenden Wassers aufgelassen und auf der .... .

Ernst Hinterberger (Wenen, 17 oktober 1931)

De Russische dichter en schrijver Anatoli Pristavkin werd geboren op 17 oktober 1931 in Ljuberzy. Zie ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2008 en ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2009.

Uit: The Inseparable Twins (Vertaald door Michael Glenny)

. . . Next morning they were woken earlier than usual, at six oclock.

Even Musa was made to get dressed, as he too was being sent away. Only the blind boys were staying behind. When the others were all being lined up to be taken to the station, Antosha appeared and shouted, Kuzmin Twins! Are you here? Are you here?

'Antosha! cried Kolka, and dashed out of the ranks.

Antosha found Kolkas hand and gave him a piece of paper. It was pierced with with the bumps in which the language of the blind is written. There it tells your fortune! saud Antosha, smiling somewhere into space, as only he blind smile.

But I cant read whats written on it!

If you ever come to our town, go to the market! said Antosha. Ill be there! Ill read it to you! You are a good person, Kolka!

Line up, children! Olga Khristoforovna shouted; this was aimed at Kolka, Everyone follow me!

It was cold in the street. A chill wind was blowing. The station was deserted. The choldren were put on the train, in an empty, dirty, uncleaned carriage. Apart from them, nobody was travelling on that first day of the new year.

Kolka showed Alhuzur the top two bunks and said, Those are ours. Sashka and I used to travel up there.

Just then Olga Khristoforovna came into the carriage and shouted, Kolka! Somebode is asking for you!

Who is it? Kolka grumbled, unwilling to leave Alhuzur.

Go outside and youll find out! said Olga Khristoforovna. With her slow, ponderous gait she moved on down the carriage, checking to see that everyone was property settled.

Are you cold, Musa? she asked the Tartar.

Musa was shivering, but he did not want to complain, being so delighted that he, too, was going away; anything was better than being left behind on his own . . .

Kolka went out on to the open platform at the end of the carriage, and there he saw Regina Patrovna. She was holding two parcels.

She run towards Kolka, but stumbled. He watched her, looking down from the carriage-platform, as she hastily climbed up the awkward little iron steps, almost dropping the parcels.

There! she said, panting breathlessly. These are your clothes the things I gave to you and Sashka on your birthday. Since Kolka made no response, she ended imploringly, Take them! When youre in your new home . . . And she put the parcels down beside Kolka on the platform floor.

They looked at each other in silence.

Anatoli Pristavkin (17 oktober 1931 11 juli 2008)

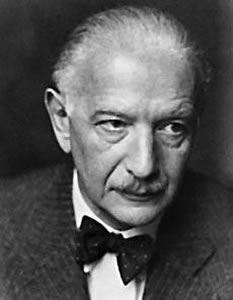

De Oostenrijkse schrijver, vertaler en criticus Alfred Polgar werd geboren op 17 oktober 1873 in Wenen. Zie ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2008 en ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2009.

Uit: Der Dienstmann

(Ich hatte gleich den Glattrasierten in Verdacht!) Der Apotheker schenkte meinem Freund als Ersatz einen alten Holzschemel aus der Küche. Der Dienstmann benutzte ihn zwei Tage lang, dann stellte

er das Geschenk dem Spender zurück. Warum? Auf der Bank war oft neben dem Dienstmann der närrische Bettler gesessen, die Hände um den Griff seines Knotenstocks und den grauen Vollbart auf die Hände gelegt.

Verstehen Sie? Der Schemel hatte nur für einen Platz. Vor der Sentimentalität, selbst zu stehen und den Bettler sitzen zu lassen, scheute der geschmackvolle Dienstmann zurück. Das Umgekehrte wiederum vertrug sein gutes Herz nicht. Also schaffte er den Schemel ab. Der Held eines Hamsunschen Romans hätte nicht feiner handeln können.

Eines Tages anno diaboli 1918 war mein Dienstmann fort. Die Zeit verging, er kam nicht wieder. Ich dachte: Gewiß ist er tot. Er war ja schon sehr elend, der alte Bucklige. Oft, wenn er unter einer Paar-Kilo-Last keuchte, sagte er: »Ich taug gar nichts mehr.« Wie alt mag er gewesen sein? So zwischen vierzig und hundert.

Die Patina der Mühsal und Entbehrung auf solchem Antlitz macht eine Altersbestimmung schwer. Gewiß ist er tot. Gewiß hat ihm der Herr, der die Spatzen nährt und die Lilien kleidet und dafür sorgt, daß die Dienstmänner nicht in den Himmel wachsen, gesagt: Vierhundertneunundzwanziger, glaubst du nicht, daß es an der Zeit wäre, deinen Standplatz mit einem Liegeplatz zu vertauschen? Und der Dienstmann 429 hat natürlich geantwortet: »Wie der Herr meinen.« Aber er war nicht zu den himmlischen Heerscharen eingerückt, sondern zur k. k. Infanterie, was freilich auf dasselbe hinauskam.

Eines Tages stand plötzlich wieder sein abhanden gekommenes, schwarz und hohl gesessenes Bänkchen vor der Apotheke. Und darauf saß, breit, der Glattrasierte. Und neben ihm an der Wand lehnte der Bettler mit dem Knotenstock. Und durfte sich nicht niedersetzen!

So ist das Leben.

Alfred Polgar (17 oktober 1873 - 24 april 1955)

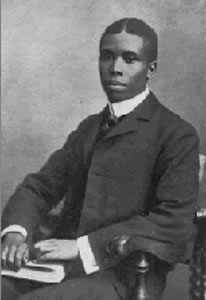

De Amerikaanse dichter Jupiter Hammon werd geboren op 17 oktober 1711. Zie ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2006 en ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2008 en ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2009.

A Poem for Children with Thoughts on Deathby

I

O Ye young and thoughtless youth,

Come seek the living God,

The scriptures are a sacred truth,

Ye must believe the word.

Eccl. xii. 1.

II

Tis God alone can make you wise,

His wisdoms from above,

He fills the soul with sweet supplies

By his redeeming love.

Prov. iv. 7.

III

Remember youth the time is short,

Improve the present day

And pray that God may guide your thoughts,

And teach your lips to pray.

Psalm xxx. 9.

IV

To pray unto the most high God,

And beg restraining grace,

Then by the power of his word

Youl see the Saviours face.

Jupiter Hammon (17 oktober 1711 - 1790 1806)

De Amerikaanse schrijver Nathanael West werd geboren op 17 oktober 1903 in New York als Nathan Wallenstein Weinstein. Zie ook mijn blog van 17 oktober 2008.

Uit: Miss Lonelyhearts

Perhaps I can make you understand. Lets start from the beginning. A man is hired to give advice to the readers of a newspaper. The job is a circulation stunt and the whole staff considers it a joke. He welcomes the job, for it might lead to a gossip column, and anyway hes tired of being a leg man. He too considers the job a joke, but after several months at it, the joke begins to escape him. He sees that the majority of the letters are profoundly humble pleas for moral and spiri- tual advice, that they are inarticulate expressions of genuine suffering. He also discovers that his correspondents take him seriously. For the first time in his life, he is forced to examine the values by which he lives. This examination shows him that he is the victim of the joke and not its perpetrator.

(...)

Dear Miss Lonelyhearts--

I am sixteen years old now and I dont know what to do and would appreciate it if you could tell me what to do. When I was a little girl it was not so bad because I got used to the kids on the block makeing fun of me, but now I would like to have boy friends like the other girls and go out on Saturday nites, but no boy will take me because I was born without a nose--although I am a good dancer and have a nice shape and my father buys me pretty clothes.

I sit and look at myself all day and cry. I have a big hole in the middle of my face that scares people even myself so I cant blame the boys for not wanting to take me out. My mother loves me, but she crys terrible when she looks at me.

What did I do to deserve such a terrible bad fate? Even if I did do some bad things I didnt do any before I was a year old and I was born this way. I asked Papa and he says he doesnt know, but that maybe I did something in the other world before I was born or that maybe I was being punished for his sins. I dont believe that because he is a very nice man. Ought I commit suicide?

Sincerely yours,

Desperate

Nathanael West (17 oktober 1903 22 december 1940)

|