|

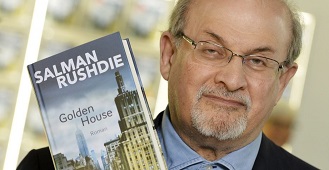

De Indisch-Britse schrijver en essayist Salman Rushdie werd geboren in Bombay op 19 juni 1947. Zie ook alle tags voor Salman Rushdie op dit blog.

Uit: The Golden House

“On the day of the new president's inauguration, when we worried that he might be murdered as he walked hand in hand with his exceptional wife among the cheering crowds, and when so many of us were close to economic ruin in the aftermath of the bursting of the mortgage bubble, and when Isis was still an Egyptian mother-goddess, an uncrowned seventy-something king from a faraway country arrived in New York City with his three motherless sons to take possession of the palace of his exile, behaving as if nothing was wrong with the country or the world or his own story. He began to rule over his neighborhood like a benevolent emperor, although in spite of his charming smile and his skill at playing his 1745 Guadagnini violin he exuded a heavy, cheap odor, the unmistakable smell of crass, despotic danger, the kind of scent that warned us, look out for this guy, because he could order your execution at any moment, if you're wearing a displeasing shirt, for example, or if he wants to sleep with your wife. The next eight years, the years of the forty-fourth president, were also the years of the increasingly erratic and alarming reign over us of the man who called himself Nero Golden, who wasn't really a king, and at the end of whose time there was a large—and, metaphorically speaking, apocalyptic—fire.

The old man was short, one might even say squat, and wore his hair, which was still mostly dark in spite of his advanced years, slicked back to accentuate his devil's peak. His eyes were black and piercing, but what people noticed first—he often rolled his shirtsleeves up to make sure they did notice—were his forearms, as thick and strong as a wrestler's, ending in large, dangerous hands bearing chunky gold rings studded with emeralds. Few people ever heard him raise his voice, yet we were in no doubt that there lurked in him a great vocal force which one would do well not to provoke. He dressed expensively but there was a loud, animal quality to him which made one think of the Beast of folktale, uneasy in human finery. All of us who were his neighbors were more than a little scared of him, though he made huge, clumsy efforts to be sociable and neighborly, waving his cane at us wildly, and insisting at inconvenient times that people come over for cocktails. He leaned forward when standing or walking, as if struggling constantly against a strong wind only he could feel, bent a little from the waist, but not too much. This was a powerful man; no, more than that—a man deeply in love with the idea of himself as powerful. The purpose of the cane seemed more decorative and expressive than functional. When he walked in the Gardens he gave every impression of trying to be our friend. Frequently he stretched out a hand to pat our dogs or ruffle our children's hair. But children and dogs recoiled from his touch.”

Salman Rushdie (Bombay, 19 juni 1947)

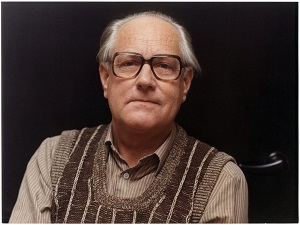

De Nederlandse dichter en schrijver Sybren Polet (pseudoniem van Sybe Minnema) werd geboren in Kampen op 19 juni 1924. Zie ook alle tags voor Sybren Polet op dit blog.

Stopwoord

Ik vond een oorschelp in de grond

om aan te luisteren.

ik luisterde en vond

drie takken taal

een drietakttaal voor één gedicht.

daar is geen zin mee te verrichten.

ik stop dat oor maar met een stopwoord dicht.

De dichter als dokter

Klop klop.

Hier komt de dokter met zijn woorden,

als een vriendelijk geklede avond,

een avond in sportkostuum.

Zeg maar niets.

Ik zal de pijn wegzuigen uit je wang

en als je wilt

leg ik mij op je als een warm compres.

Zo wen je misschien misschien gemakkelijker aan je lichaam.

Ben je alleen? Stel je maar voor:

iedere minuut treed ik opnieuw de kamer binnen,

ik steek de lamp aan en schik je bed;

één woord leg ik op je voorhoofd

als een hand koel ijs,

twee woorden duw ik als kussens in je rug,

één woord laat ik achter om je te strelen.

Zo heeft mijn gedicht toch een funktie.

En als je wakker wordt en wilt drinken,

twee jonge in het wit gestoken woorden geven je te drinken

en als je slapen wilt

dit is een woord zó zacht

dat je wel moet slapen.

Als zulke woorden zou ik om je willen zijn.

Klop, klop

hier komt de dokter met zijn woorden.

Sybren Polet (19 juni 1924 – 19 juli 2015)

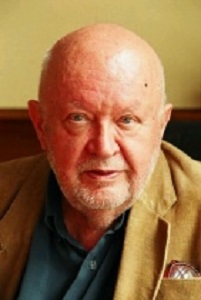

De Tsjechische schrijver Josef Nesvadba werd geboren op 19 juni 1926 in Praag. Zie ook alle tags voor Josef Nesvadba op dit blog.

Uit: The Half-wit of Xeenemuende (Vertaald door Iris Unwin)

“The unfortunate teacher always counted the minutes to suppertime; never in all his life had lessons seemed so long, and never before had he felt so reluctant to go and teach his pupils.

About a month later he caught sight of Bruno fighting a gang of younger children in the street. He was attacking a couple of eight-year-olds, tripping them up and then kicking them when they were down.

"Bruno!" he shouted from a way off, but he couldn't run because he had trouble with his breathing, and so it was the butcher's wife who dealt with Bruno because she had seen the whole thing from her shop. She grabbed the boy by the collar -- she was a muscular woman -- and just lifted him over the fence into the Habichts' garden. Then she took the other children indoors and washed their grazes for them.

"He's always doing things like that," she explained to the horrified teacher. "An idiot, that's what he is. Ought to be in a Home. If his father wasn't such a big bug they'd have taken him away long ago. Everybody's surprised at you going there at all."

It was a particularly good supper at the Habichts' that evening, though, and he could even taste a hint of real coffee in the ersatz. Even Bruno was behaving quietly, only staring sulkily at one spot in the corner of the room. And so the old man could not bring himself to give notice.

That night the whole town was roused by another catastrophe. The butcher's shop opposite the Habichts' was destroyed the very same way as the governess's house had been: by a small-calibre bomb or an artillery shell. The missile must have passed in through the window, and exploded inside the room, demolishing it. The shop was burned down.

Next day Bruno was smiling all through his lesson. The teacher began to feel uneasy.

"Who looks after your boy all day?" he carefully approached Mrs. Habicht at supper-time.

"Nobody. He's awfully good. He spends all his time on the veranda at the back of the house. His father put together a little workshop for him to potter about in."

"I'd like to see that."

"No!" the boy blurted out in a low, furious voice, and his face darkened."

Josef Nesvadba (19 juni 1926 – 26 april 2005)

De Japanse schrijver Osamu Dazai (eig.Shūji Tsushima) werd geboren op 19 juni 1909 in Tsugaru. Zie ook alle tags voor Osamu Dazai op dit blog.

Uit: The setting sun (Vertaald door Donald Keene)

„I have never liked breakfast and am not hungry before ten o'clock. This morning I managed to get through the soup, but it was an effort to eat anything. I put some rice-balls on a plate and poked at them with my chopsticks, mashing them down. I picked up a piece with my chopsticks, which I held at right angles to my mouth, the way Mother holds a spoon while eating soup, and pushed it into my mouth, as if I were feeding a little bird. While I dawdled over my food, Mother, who had already finished her meal, quietly rose and stood with her back against a wall warmed by the morning sun. She watched me eating for a while in silence.

"Kazuko, you mustn't eat that way. You should try to make breakfast the meal you enjoy most."

"Do you enjoy it, Mother?"

"It doesn't matter about me — I'm not sick anymore."

"But I'm the one who's not sick."

"No, no." Mother, with a sad smile, shook her head.

Five years ago I was laid up with what was called lung trouble, although I was perfectly well aware that I had willed the sickness on myself. Mother's recent illness, on the other hand, had really been nerve-racking and depressing. And yet, Mother's only concern was for me.

"Ah," I murmured.

"What's the matter?" This time it was Mother's turn to ask.

We exchanged glances and experienced something like a moment of absolute understanding. I giggled and Mother's face lighted into a smile.

Whenever I am assailed by some painfully embarrassing thought, that strange faint cry comes from my lips. This time I had suddenly recalled, all too vividly, the events surrounding my divorce six years ago, and before I knew it, my little cry had come out. Why, I wondered, had Mother uttered it too? It couldn't possibly be that she had recalled something embarrassing from her past as I had. No, and yet there was something.

"What was it you remembered just now, Mother?"

Osamu Dazai (19 juni 1909 – 13 juni 1948)

Cover

De Filippijnse dichter en schrijver José Rizal (eig. José Protacio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda) werd geboren op 19 juni 1861 in Calamba. Zie ook alle tags voor José Rizal op dit blog.

Flower Among Flowers

Flower among flowers,

soft bud swooning,

that the wind moves

to a gentle crooning.

Wind of heaven,

wind of love,

you who gladden

all you espy;

you who smile

and will not sigh,

candour and fragrance

from above;

you who perhaps

came down to earth

to bring the lonely

solace and mirth,

and to be a joy

for the heart to capture.

They say that into

your dawn you bear

the immaculate soul

a prisoner

-- bound with the ties of

passion and rapture?

They say you spread

good everywhere

like the Spring

which fills the air

with joy and flowers

in Apriltime.

They say you brighten

the soul that mourns

when dark clouds gather,

and that without thorns

blossom the roses

in your clime.

If then, like a fairy,

you enhance

the joy of those

on whom you glance

with the magic charm

God gave to you;

oh, spare me an hour

of your cheer,

a single day

of your career,

that the breast may savor

the bliss it knew.

José Rizal (19 juni 1861 – 30 december 1896)

Standbeeld in Fort Santiago

De Duitse dichter en schrijver Friedrich Huch werd geboren op 19 juni 1873 in Braunschweig. Zie ook alle tags voor Friedrich Huch op dit blog.

Uit: Pitt und Fox

„Wurde Fox am Ende seiner Erzählungen König, so verscholl Pitt am Schlusse ganz und gar und wußte selbst nicht, wo er blieb. – In solchen Augenblicken schwelgte Fox im Gefühle seiner eingebildeten Stärke. Herr Sintrup aber sagte: Aus dir wird mal was Großes! Aber du, Pitt, kannst dich nur gleich begraben lassen. – Dann zog Pitt unbemerkt ein Taschenbüchlein hervor, suchte eine bestimmte Seite und machte einen Bleistiftstrich. Sein Vater und seine Mutter sagten stets dasselbe, und er führte darüber eine Art Statistik.

Herr Sintrup war ein rühriger, geachteter Fabrikant in dem kleinen Städtchen. Pünktlich mit dem Glockenschlag war er zumeist im Bureau und schnauzte seinen Angestellten ein gutmütiges «Guten Morgen» zu. Nur manchmal kam es vor, daß er im Bett länger liegenblieb, denn ab und zu liebte er einen «guten Tropfen», wie er das nannte. Bekam er einen neuen Lehrling, so stellte er ihn vor sich hin, durchbohrte ihn mit seinen Augen und sagte in schrecklich drohendem Ton: Bengel, Bengel, ich sage dir...! Im Grunde aber war er gutmütig und leicht gerührt.

Fox fühlte sich in seiner Haut sehr wohl; den Dienstboten gegenüber tat er, als sei er eigentlich eine Art von Kronprinz; seine Mutter hatte er ganz in der Gewalt, sie verwöhnte ihn und gab ihm in allem seinen Willen, um so mehr, als Pitt ihr nicht im Wege war, der nie um etwas bat und mit einem stereotypen Danke alles in Empfang nahm, mochte es nun Gutes oder Geringwertiges sein.

Pitt erschien wie ein verschlossenes, etwas impertinentes Waisenkind, das trotz aller jahrelangen Gewöhnung niemals recht häuslich wird in dem Kreise seiner Pflegeltern. Die Namen seiner nächsten Verwandten konnte er nicht auseinanderhalten. Manchmal mußte er sich erst besinnen, wo das Eßzimmer, wo die Wohnstube lag. Genau so fremd lebte er in der Schule. Seinen Kameraden gegenüber hatte er einen leise überlegenen, ironischen Ton, feiner oder plumper, je nachdem er es für angemessen hielt. Wirkliche Freundschaften kannte er nicht. Er litt darunter, konnte es aber nicht ändern. Einmal schloß er sich an eine gleichaltrige Kusine an; aber das Mädchen wurde so gefühlvoll, ihm war, als spielten sie Theater; und als sie ihn eines Tages wie gewöhnlich besuchen wollte, fand sie seine Tür verschlossen, und er rief ihr durchs Schlüsselloch zu, es sei aus zwischen ihnen, er wolle sie nie wiedersehen. Als er dann später einmal ein tragisch auf ihn gerichtetes Gesicht erblickte, mußte er sich erst besinnen, wer das war.“

Friedrich Huch (19 juni 1873 – 12 mei 1913)

Cover

De Duitse dichter, schrijver en pastor Gustav Schwab werd geboren op 19 juni 1792 in Stuttgart. Zie ook alle tags voor Gustav Schwab op dit blog.

Die stille Stadt

Nenne mir die stille Stadt,

Die den ew'gen Frieden hat,

Deren düstere Gemächer

Sanft sich bauen grüne Dächer:

Ueber ihrer Häuser Zinne

Wandelt ernst der Fremdling hin,

Ziehet fort und hält nicht inne,

Grauen fasset ihm den Sinn.

Aber endlich tritt er wieder

Zitternd auf das morsche Dach,

Und die Wölbung sinket nieder,

Daß er stürzt in das Gemach.

Drunten in den Hallen traurig

Sieht er da die Bürger ruhn,

Alle liegen stumm und schaurig,

Mögen keinen Gruß ihm thun.

Die geschlossne Pforte kündet

Ihm sein ewig Bürgerrecht,

Und der arme Wandrer findet

Bald ein Bettlein recht und schlecht,

Ist des Prunkens müde worden,

Schickt sich in den stillen Orden,

Legt sich nieder in der Stadt,

Die den ew'gen Frieden hat.

Sonette aus dem Bade 1835

1

Was liegt der Schlaf auf meinen Augenlidern

Am hellen Tag? was ist mein Haupt so schwer?

Bald ras't mein Puls, bald find' ich ihn nicht mehr!

Pickt schon der Totenwurm in meinen Gliedern?

»Du bist nicht krank!« hör' ich den Arzt erwiedern

Auf dieser Klagen ungestümes Heer.

»Setz' gegen deine Bücher dich zur Wehr!

Laß dir den trägen Mut Natur befiedern!

Geh' in ein Bad, doch hüte dich zu baden;

Zum Brunnen, doch das Glas nicht an den Mund,

Viel lieber laß zum Firnewein dich laden.

Hinab zur Kühle, dort im Felsengrund!

Empor im Schweiß auf steilen Tannenpfaden,

Lern' wieder leben, und du wirst gesund!

Gustav Schwab (19 juni 1792 – 4 november 1850)

Stuttgart, Ansicht von Südosten. Gravure door C. Gerstner naar H. Schönfeld, ca. 1870

Onafhankelijk van geboortedata:

De Nederlandse schrijfster Elke Geurts werd geboren in Heijen in 1973. Zij studeerde aan de Hogeschool voor de Kunsten in Utrecht. Ze schreef toneelstukken en hoorspelen alvorens ze doorbrak met korte verhalen. Zij was de eerste winnaar van de verhalenwedstrijd Duizend Woorden en won de Nieuw Proza Prijs Venlo 2008Geurts publiceerde de verhalenbundels “Het besluit van Dola Korstjens” (2008), “Lastmens” (2010) en “Lastmens & andere verhalen” (2015), en de veelgeprezen roman “De weg naar zee” (2013). Haar werk werd genomineerd voor onder andere De Gouden Boekenuil, de BNG Literatuurprijs en de Anna Bijns Prijs. Geurts is schrijfdocent aan o.a. Schrijversvakschool Amsterdam, en columniste en recensent buitenlandse fictie voor Trouw.

Uit: Ik nog wel van jou

“Ik vroeg of hij de titel die mijn nieuwe uitgever had bedacht goed vond. ‘Veel te plat,’ zei ik. ‘Dat kan écht niet, toch?’

We hingen tegen het aanrecht in onze keuken met onze armen over elkaar en praatten over het werk en de kinderen, maar niet over de zakelijke mail die we om kwart over negen in de ochtend beiden hadden ontvangen. Met het stappenplan.

We hadden uitzicht op onze kleine entreehal en keken naar de jassen aan, op en onder de kapstok; een plank met haakjes die man zelf had gemaakt toen we hier kwamen wonen. Mijn vader ergert zich er al jaren aan dat er in ons nieuwbouwhuis niets waterpas is.

‘Alles wat dat jong hier zelf timmert is waardevermindering.’

We zagen een onordelijke berg schoenen, heely’s, skeelers en één groezelig grijze slof, daarnaast de uitpuilende rieten mand vol ongelezen kranten en wijnfl essen, erg veel lege wijnflessen.

Die grijze afgedragen sloff en staan nu nóg overal waar ik kijk, alsof er hier in huis een onzichtbaar mannetje achter me aan sloft dat ze – waar ik ook zit of sta – steeds precies in mijn zicht legt.

Op dit punt van het verhaal bevonden we ons in de donkere dagen voor kerst, een ijskoude wind kwam naar binnen, maar man had de deur naar het halletje wijd open laten staan, zo ook onze voordeur. Wagenwijd. Het lelijkste standaardmodel, met vier horizontale ramen waar ik de afgelopen anderhalf jaar nogal vaak – kromgebogen – doorheen had staan kijken. Zoals de buurvrouwen in het dorp waar ik vandaan kom vroeger altijd door de jaloezieën gluurden om te kijken wie er thuiskwam en wie er wegging, zo stond ik daar op die ingelegde droogloopmat de straat af te speuren. Te wachten. Op man.”

Elke Geurts (Heijen, 1973)

De Duitse dichteres Claudia Gabler werd in 1970 geboren in Lörrach. Zie ook alle tags voor Claudia Gabler op dit blog.

Eigentlich hatte ich gehofft, der Bus sei schon abgefahren.

Ich hatte ja keine Ahnung von den Rokokokirchen und

ihren egozentrischen Lichtspielen. Dich dagegen befriedigt es

offensichtlich völlig, wenn eine Taube sich aus den Glocken

schlägt, so wie wir damals dachten, wir wüßten alles über

das Leben und diese albernen Raclettegeräte. Heute weiß

ich zumindest, daß wir jahrelang neben einem berühmten

Hirnchirurgen gewohnt haben, ohne auch nur seinen Namen

zu kennen. Im Nachhinein bin ich mir sicher, daß er

ein guter Gesprächspartner gewesen wäre.

Ja, es ist wahr, von der Natur können wir so manches über

Ordnung lernen. Und ich meine nicht die Ordnung, die sich

ständig wiederholt und deshalb langweilig ist. Sondern ich

meine die komplexe Ordnung der Welt der Dinge, in der wir

leben. Also das Chaos als subtilere, nicht wiederkehrende

Art von Ordnung.

Schreibst du das alles auf? Rufst du mich an, wenn du

wiederkommst von dem Kontinent, der dich aufbläht wie

einen Mathematiker, der über seiner Arbeit verzweifelt?

Ich wünschte, wir hätten noch etwas von dem Käse da,

den wir im Morgengrauen in der alten Markthalle

neben der Themse gekauft haben. Als du am anderen

Ende der Welt am Fenster standst und ein Insekt

aus deinem Auge riebst.

Claudia Gabler (Lörrach, 1970)

|