|

De Spaanse dichter en toneelschrijver Federico Garcia Lorca werd geboren op 5 juni 1898 in Fuente Vaqueros, Granada. Zie ook alle tags voor Federico Garcia Lorca op dit blog.

Lament for the Death of Ignacio Sánchez Mejías

1. Goring And Death

At five in the afternoon.

It was five sharp in the afternoon.

A boy brought the white sheet

at five in the afternoon.

A basket of lime already set

at five in the afternoon.

The rest was death and only death

at five in the afternoon.

The wind swept away the cotton

at five in the afternoon.

And rust planted crystal and nickel

at five in the afternoon.

Now the struggle of leopard and dove

at five in the afternoon.

And a thigh with a desolate horn

at five in the afternoon.

And so began the bass notes

at five in the afternoon.

The arsenic bells and the smoke

at five in the afternoon.

On the corners groups of silence

at five in the afternoon.

And the bull alone with heart on high

at five in the afternoon.

When the sweat of snow arrived

at five in the afternoon,

when the bullring filled with iodine

at five in the afternoon,

death laid eggs in the wound

at five in the afternoon.

At five in the afternoon.

At five sharp in the afternoon.

The bed is a coffin on wheels

at five in the afternoon.

Bones and flutes blow in his ear

at five in the afternoon.

The bull bellowed on his brow

at five in the afternoon.

The room iridescent with agony

at five in the afternoon.

Gangrene comes in the distance

at five in the afternoon.

Trumpet of lilies on green groins

at five in the afternoon.

The wounds burned like suns

at five in the afternoon,

and the rabble broke the windows

at five in the afternoon.

Oh, what a terrible five in the afternoon!

It was five on all the clocks.

It was five in shadow of the afternoon.

2. Spilled Blood

I don’t want to see it!

Tell the moon to come.

I don’t want to see

Ignacio’s blood on the sand.

I don’t want to see it!

The moon fully open,

a horse of quiet clouds

and the gray bullring of sleep

with willows over the barricades.

I don’t want to see it!

My memory burns.

Warn the jasmine

to cover its whiteness!

I don’t want to see it!

The cow of the old world

stroked a snout of blood

with its sorrowful tongue

and the bulls of Guisando

almost death and almost stone

bellowed like two centuries

tired of walking the land.

No.

I don’t want to see it.

Up the bleachers goes Ignacio

with death on his shoulders.

He looks for dawn

and it isn’t dawn.

He looks for his sensible profile

and sleep confuses him.

He looks for his beautiful body

and finds his open blood.

Don’t ask me to see it!

I don’t want to feel the spurt

growing weaker by the moment,

the spurt that illumines

the seats and spills

on the hide of the thirsty crowd.

Who orders me to look!

Don’t make me see it!

His eyes didn’t close

when he saw the horns approach,

but the terrible mothers

raised their heads

and all through the cattle ranches

there was an air of secret orders

thrown to celestial bulls

by the foremen of pale mists.

There wasn’t a prince in Seville

who could compare,

no sword like his sword

nor a heart so real.

His strength was a river of lions,

his prudence a torso of marble.

An air of Andalusian Rome

gilded his head

where his smile was a rose

of salt and intelligence.

The great fighter of bulls!

The good mountaineer of the mountain!

How soft with the wheat stalk!

How hard with his spurs!

How tender with the dew!

How dazzling in the fair!

How grand with the last

banderillas of dusk!

But now he sleeps forever.

Now the grass and the moss

open with sure fingers

the flower of his skull.

And his blood comes singing:

singing through marshes and prairies,

sliding down shivering horns,

wandering soulless in fog,

stumbling on thousands of hoofs

like a long, dark, sorrowful tongue

to form a puddle of agony

by the Guadalquivir of the stars.

Oh white wall of Spain!

Oh black bull of sorrow!

Oh hard blood of Ignacio!

Oh nightingale of his veins!

No.

I don’t want to see it!

There is no chalice to hold it.

There are no swallows that drink it,

no frost of light to cool it,

no song or deluge of lilies,

no crystal to bathe it in silver.

No.

I don’t want to see it!

Vertaald door Pablo Medina

Federico García Lorca (5 juni 1898 – 19 augustus 1936)

Muurschildering in New York

De Nederlandse dichter en schrijver Adriaan Morriën werd geboren op 5 juni 1912 in Amsterdam. Zie ook alle tags voor Adriaan Morriën op dit blog.

Lectuur

Ik kan niet genoeg krijgen van je huid.

Als een blinde lees ik met mijn vingers

het stille verhaal van je oppervlak.

In je ogen dreig ik te verzinken.

Op je huid bewandel ik alle wegen

zonder mij van jou te verwijderen.

Soms keer je je behulpzaam op je buik.

Je rug is een lang hoofdstuk uit een boek.

Ik spel je tepels, herlees je oren.

Ik laat je tenen op elkander rijmen.

Ik lees tussen de regels van je benen

en blader in de atlas van je hals.

Het is mij of mijn eigen vingers

je lichaam hebben uitgeschreven.

Eerst viel het mij als klank te binnen,

toen lag het als een beeldspraak op mijn tong

en nu herhaal ik wat ik heb gestameld

in vloeiende bewoordingen.

Schilderij

Twee doode kreeften met gebroken scharen

Rood op de witheid van het tafellaken;

Een gele wijn, die fonkelt in het glas,

Maar niet gedronken wordt; gemorste asch,

En tusschen appelen en eierschalen

Een houten kruisbeeld met de pijn en zegen

Van zijn doorboorde handen. In den regen,

Achter het raam, dat uitziet in de straat,

Het grijs gelaat van een bedroefde vrouw,

Die in den rouw van hare kleeren staat,

Verwonderd en afwijzend en naijvrig

En ongetemd: haar wilde armen slaan,

Als in een dwaas verweer langs 't vensterraam.

En verder in een kleinen, kalen tuin

Van een der huizen aan den overkant,

Zacht neergevlijd als een vermoeide hand,

Een laatst verzet in 't wijkend perspectief,

De weemoed van een omgewaaiden boom.

Adriaan Morriën (5 juni 1912 – 7 juni 2002)

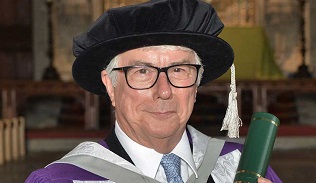

De Engelse schrijver Ken Follett werd geboren op 5 juni 1949 in Cardiff, Wales. Zie ook alle tags voor Ken Follett op dit blog.

Uit:Het eeuwige vuur(Vertaald door Joost van der Meer en William Oostendorp)

“Te midden van een sneeuwstorm kwam Ned Willard thuis in Kingsbridge.

In de hut van een trage schuit, geladen met stoffen uit Antwerpen en wijn uit Bordeaux, voer hij stroomopwaarts vanuit Combe Harbour.

Toen hij vermoedde dat de boot eindelijk Kingsbridge naderde sloeg hij zijn Franse mantel strakker om zijn schouders; hij trok de capuchon over zijn oren, stapte het open dek op en tuurde in de verte.

Aanvankelijk werd hij teleurgesteld: vallende sneeuw was het enige wat hij zag. Maar zijn verlangen om een glimp van de stad op te vangen was als een pijn, en vol hoop staarde hij in de sneeuwvlagen. Na een poosje werd zijn wens vervuld, de storm begon zich terug te trekken. Er verscheen een verrassend stukje blauw aan de hemel. Starend over de toppen van de omringende bomen zag hij de toren van de kathedraal, honderddrieentwintigenhalve meter hoog, zoals iedere leerling in Kingsbridge

wist. De stenen engel die vanaf de torenspits over de stad waakte had vandaag sneeuw op haar vleugels liggen, waardoor haar duifgrijze vleugeltoppen nu helderwit waren. Even viel er een zonnestraal op het beeld, die als een zegen van de sneeuw af fonkelde; daarna sloot de storm haar weer in en werd ze aan het zicht onttrokken.

Een poosje zag hij niets anders dan bomen, maar zijn verbeelding liep over. Hij stond op het punt om na een afwezigheid van een jaar met zijn moeder te worden herenigd. Hij zou haar niet vertellen hoezeer hij haar had gemist, want een man diende op zijn achttiende onafhankelijk te zijn.

Maar bovenal had hij Margery gemist. Hij was op een rampzalig moment voor haar gevallen: een paar weken voor zijn vertrek uit Kingsbridge om een jaar door te brengen in Calais, de door Engelsen bestuurde havenstad aan de Franse noordkust. Hij kende en mocht de ondeugende, intelligente dochter van sir Reginald Fitzgerald al sinds zijn kindertijd.

Toen ze opgroeide had haar schalksheid een nieuwe verleidelijkheid gekregen, waardoor hij merkte dat hij in de kerk met een droge mond en oppervlakkige ademhaling naar haar staarde. Hij had geaarzeld om meer te doen dan alleen staren, want ze was drie jaar jonger dan hij, maar zij kende zulke remmingen niet. Op het kerkhof van Kingsbridge, achter de grote graftombe van prior Philip, de monnik die vier eeuwen eerder de opdracht voor de bouw van de kathedraal had gegeven, hadden ze elkaar gekust. Er was niets kinderachtigs geweest aan hun lange, gepassioneerde zoen; daarna had ze gelachen en was ze weggerend.”

Ken Follett (Cardiff, 5 juni 1949)

De Britse dichter en schrijver Paul Farley werd geboren op 5 juni 1965 in Liverpool. Zie ook alle tags voor Paul Farley op dit blog.

Ports

1

I want you to imagine, in your late capitalist's mind's eye,

a stagnant fly-blown lake under an African sun,

the smell of the sea just beyond (this at least should come easy

being the universal saltwater of all your childhoods).

Armies of ants on parade in the poor weeds and grey sludge

of the ages, dismantling the scene in their own time-lapse movie,

skeletal cats picking over spoil, boneyard mongrels

marking their range by the water's edge before moving on.

I want you to imagine all this, because once I was Carthage

and still am in name, though like some poisoned inland sea

my horizons have shrunk to a port that handles zero tonnage,

an import and export that evens the scales up at nil,

not counting the old rope and plastic bottles that come knocking

with the tides, not counting the rusted tins that drift in,

not counting the ants shifting clay forms and Carrera marble

from my ruins, or the guide who conducts his own private dig

for unscrupulous tourists who think nothing of removing

a coin from its context (if money ever has such set contexts),

of taking a Roman penny with an obverse of Augustus

out of the country, to reach the cold northern latitudes

in the holds of Lufthansa or Aeroflot, in a fraction

of the time it once took under oar and Ursa Major.

I was Carthage, but nothing much comes or goes in this afterwards;

all that's left of a thousand years of dockyards and shipsheds

are a few shapes the soft earth has found indigestible,

for the tourist to squint at, consider, weigh up, reconstruct

imaginatively, as I am asking you, listener.

From this silted salt lake I once pulled the strings of the known world.

Lovers looked out from my sea walls into powerful distance

that bound them knowing that I was a true centre.

They pulled tight their merchant purses. They drank from clay pitchers -

under glass now in nearby museums. A museum will go some way

to help in your excavations, but what stories lead on from

the razors and combs and amphora and ostrich egg masks

are the details of millions who passed through, then into the ground.

Standing over a scale model in its sea of flat glass

acts out a dominion of your time over mine, looking down on

my circular dockyard apotheosis; looking down

as from a great height, in a way I can never have known.

A map might be easier in helping you build on my wasteland:

my trade routes once lit up the coastlines in thousands of oil lamps,

a Phoenician outline of Africa in the antique night,

spreading westward and hugging the shore, a luminous tracing

that brought in and foundered sea creatures, signalling for their mates.

I can still taste the distant metals like blood in my harbour mouth,

the tin and the iron and the copper which don't come here now

but leech down the well-furrowed sea lanes, my phantom nerve endings.

Carthaginian and Roman and Vandal are blinks in my brine eye,

In each of their eternities: to me they rise and fall

as sea swell. Credit me, listener, with such a long memory,

as more than the sum of my parts, more than archaeology

and soft sump, more than ground fought over. Aeneas stood here once

with a mind to call it quits and cut loose, so the story goes,

my port in his storm to his girl in every port.

The jets tilt and bank heading north for their carrier hubs

in Frankfurt and Moscow, without so much as a second thought

for me in my modern darkness, their starboard wing lights

blinking in an element I knew nothing about.

Some things have endured: the peaks of Cap Bon across the bay

form a backdrop to nothing much doing these days; the stars rise

to guide nobody from my mouth and on course for the Pillars

of Hercules - but these things give me a sense of myself,

as the winds do, strong at the turns in the year, which remind me

of cargoes and freights in their seasons, gross tonnes that passed through

as sand through an hour glass, until history,

like the idea of magnetic north so long in the discovering,

moved slowly away from here, like a great ship embarking

out onto the future's broad main, and this is the fate

of all ports, even yours, listener. Listen to me. I was Carthage.

Paul Farley (Liverpool,. 5 juni 1965)

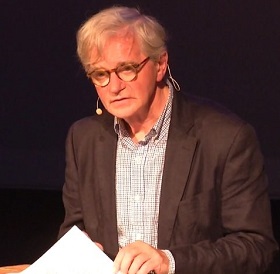

De Engelse schrijver Geoff Dyer werd op geboren 5 juni 1958 in Cheltenham. Zie ook alle tags voor Geoff Dyer op dit blog.

Uit:Broadsword Calling Danny Boy

“Meanwhile, at dusk—even allowing for the fact that it’s winter, the day has been stunningly short—the Eagles sneak across the snowy railroad tracks, in the wake of a freight train whose role will not extend beyond this cameo appearance (a sad decline from the recent glory years of Von Ryan’s Express [1965], starring Frank Sinatra, and The Train [1964], with Burt Lancaster). They let themselves into a storage unit where Eastwood and Burton strip off their parkas and pull out greatcoats and caps from their small but apparently bottomless rucksacks. They have not packed lightly, these two; they have enough clothes and equipment to keep the Sherpas on an inter-war Everest expedition employed for much of the climbing season. Working within the confines of a smaller costume budget, the others do what they can, reversing their parkas from snowy-white to wintery camouflage. Thus arrayed, like any bunch of lads on a stag weekend, they head into the village of Werfen for a bit of the old après-ski (minus the skiing), a little apprehensive, naturally, this being their first night out on the streets of the resort. The pitched roofs are laden with snow, the streets are bustling with troops and vehicles, and there’s so much parping of horns it sounds like an Alpine equivalent of Cairo.

They choose a tavern at random—we’ll try this one behind us, says Burton, though as with most things he says he’s not saying but ordering. He tells them to keep their ears open for anything about General Carnaby, but it seems a lame excuse for that which needs no excuse, namely getting into the bar and getting a few down them. It’s a cosy place with foaming steins, a really festive Bavarian atmosphere and no obviously anti-Semitic conversation. You can’t help thinking what fun it would be to attend a fancy-dress party like this in real life, even though you’d catch hell from the tabloids, especially since the guests include none other than the blond beast Von Hapen, in his medal-bedecked Gestapo costume. For once Burton is not the one doing the ordering; it’s Eastwood who orders drinks at the bar, thereby raising the possibility that, for all his swagger, command and much-publicized love of drink and his willingness to splash out vast sums of money on diamonds, Burton might be that lowest, most treacherous form of British life: a round-dodger, a conscientious-drink-buying-objector and all-round round-shirker. Even this suspicion only slightly clouds the rest of the group’s belief that this is surely the best of all Second World War mission-capers, way better than scaling the cliffs of Navarone, sweating your malarial bollocks off on that ghastly bridge over the River Kwai or waiting for Telly Savalas to flip his sicko lid in The Dirty Dozen. A top night seems guaranteed as long as they can keep up their German and not be tricked into letting their conversational guard down, as fatally happened, six years earlier, to Gordon Jackson as he boarded a bus in The Great Escape (before enjoying extended small-screen resurrections in Upstairs Downstairs and The Professionals).”

Geoff Dyer (Cheltenham, 5 juni 1958)

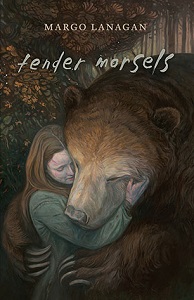

De Australische schrijfster Margo Lanagan werd geboren op 5 juni 1960 in Waratah, New South Wales. Zie ook alle tags voor Margo Lanagan op dit blog.

Uit: Tender Morsels

“Has the chimney fallen in? Or what is it?” She wanted to step farther out and look.

But he sprang over the logs and ran at her. She was too surprised to fight him, and her insides were too delicate. The icicled edge of the thatch swept down across the heavy sky, and she was on the floor, the door slammed closed above her. It was dark after the snow-glare, the air thick with the billowing smoke. Outside, he shouted—she could not hear the words—and hurled his logs one by one at the door.

She pressed her nose and mouth into the crook of her elbow, but she had already gulped smoke. It sank through to her deepest insides, and there it clasped its thin black hands, all knuckles and nerves, and wrung them, and wrung them.

Time stretched and shrank. She seemed to stretch and shrink. The pain pressed her flat, the crashing of the wood. Da muttered out there, muttered forever; his muttering had begun before her thirteen years had, and she would never hear the end of it; she must simply be here while it rose from blackness and sank again like a great fish into a lake, like a great water snake. Then Liga’s belly tightened again, and all was gone except the red fireworks inside her. The smoke boiled against her eyes and fought in her throat.

The pains resolved themselves into a movement, of innards wanting to force out. When she next could, she crawled to the door and threw her fists, her shoulder, against it. Was he out there anymore? Had he run off and left her imprisoned? “Let me out or I will shit on the floor of your house!”

There was some activity out there, scraping of logs, thuds of them farther from the door. White light sliced into the smoke. Out Liga blazed, in a dirty smoke-cloud, clambering over the tumbled wood, pushing past him, pushing past his eager face.”

Margo Lanagan (Waratah, 5 juni 1960)

Cover

De Nederlandse literair criticus Carel Peeters werd geboren in Nijmegen op 5 juni 1944. Zie ook alle tags voor Carel Peeters op dit blog.

Uit: Het eigenwijze potlood

“Of het nu om mensen of dieren ging, Peter Vos was in zijn tekeningen voortdurend aan het vermommen, om-draaien, transformeren en verkleden: dieren die menselijke din-gen doen, mensen die dierendingen doen, mensen die in vogels veranderen, wezens die half dier, half mens zijn, mensen die in een satirisch beestenkarakter veranderen (klavierleeuw, kloothom-mel). Hij was een Pulcinel, de komische bediende uit de commedia dell'arte die aan alles een fantasierijke wending moest geven. Met een handtekening in de vorm van een Pulcinel ondertekende hij vaak zijn brieven. Eind jaren vijftig sorteerde de toenmalige uitgever van De Arbei-derspers Theo Sontrop nog brieven op het postkantoor van Amster-dam. Op een dag herkende hij een met vogels versierde envelop als afkomstig van Peter Vos, net als hij oud-leerling van het St. Boni-fatiuslyceum in Utrecht Peter Vos was inmiddels student aan de Rijksakademie, Sontrop zat in de redactie van het studentenweek-blad Propria Cures. Hij vond dat Propria Cures wel een vaardig en geestig tekenaar als Peter Vos kon gebruiken. Dat dacht Rinus Ferdinandusse ook toen hij als redacteur van Propria Cures was over-gestapt naar Vrij Nederland (VN) en Vos vroeg mee te gaan. In het begin maakte Vos getekende grappen voor de rubriek 'Vrij Blijvend', die later 'Terzijde' zou gaan heten. De rubriek bestond nog uit pasti-ches en parodieën geschreven door Ferdinandusse en Hugo Brandt Corstius, en niet uit de volle kolom oneliners van Toon Verhoeven waarmee de rubriek later vermaard zou worden. vn-lezers lazen hem altijd als eerste ('Als je van lezen houdt is de Tros een goede omroep'). In die verzuilde tijd kon een tekening van Peter Vos nog voor de nodige commotie en ingezonden brieven zorgen. Zoals de tekening in het kerstnummer van het jaar 1960. Het is kerstavond en we zien Jozef op het moment dat een engel hem laat weten dat er een kindje is geboren. ''t Is een jongen!' juicht de engel. En toen in 1964 de aflevering 'Beeldreligie' van het satirische televisieprogramma Zo is het toevallig ook nog eens een keer zo veel verontwaardiging had ge-wekt, maakte Peter Vos de tekening van de man die voor de televisie zit en zijn vrouw roept 'Mien, kom. Het is weer kwetsen.' Zijn bijdrage aan 'Terzijde' bestond uit het tekenen van de weke-lijkse leeuw. Die werd zo'n vaste verschijning dat je hem bijna over het hoofd zag. Maar wie dat niet liet gebeuren, zag de mens ver-momd als leeuw elke week vechten tegen de aanvallen van het leven. Hij nam in de loop der tijd elke denkbare manhaftige pose aan. De leeuw werd met alles geconfronteerd, elke ochtend al meteen met zichzelf in de spiegel, en verder in de loop van de dag met allerhande tegenstanders die hij niet zelden met een zwaard te lijf ging, tot hij zich bedacht. “

Carel Peeters (Nijmegen, 5 juni 1944)

De Nederlandse dichter, schrijver en schilder Robert Marie Philmain Joseph Franquinet werd geboren in Amby (bij Maastricht) op 5 juni 1915. zie ook alle tags voor Robert Franquinet op dit blog.

Gedicht

Ik weet het wee van zoveel scherpe klippen.

Ik weet het lied dat druipt van wrange wijn.

Ik weet veraders aan uw fijngekorven lippen

die mij een smart van lang-verduren zijn;

want wist gij hoe ik heb gebeden

om niet meer droef uw roekloosheid te denken,

hoe 'k u wou bedden, heel schuldeloos en rein

en hoe 'k het snijdend woord voor u steeds heb vermeden

om zacht en heelend en ook goed te zijn.

Hoe ik de eenzaamheden

geregen heb tot kostbre snoeren rond uw lijf,

hoe ik het licht bevangen heb vermeden

en hoe ik stil bij 't graf van een herinnering blijf.

En hoe de stilte werd tot een ondraaglijk tarten

te weten dat er is een véélvergulden schijn!

Die kerft zijn wond in al te wilde harten

die niet bevrijd, te snel verbeten zijn...

Weet gij dat wij toch grenzeloos herleven

van dit vergift, nog zoeter dan jasmijn?

dat alles nieuw, het hunkren en het streven

en 't worstelen, ongekend, rebels en wreed zal zijn.

Robert Franquinet (5 juni 1915 – 30 mei 1979)

De Engelse schrijfster Margaret Drabble werd geboren op 5 juni 1939 in Sheffield, Yorkshire. Zie ook alle tags voor Margaret Drabble op dit blog.

Uit: The Garrick Year

“While I was watching the advertisements on television last night, I saw Sophy Brent. I have not set eyes on her for some months, and the sight of her filled me with a curious warm mixture of nostalgia and amusement. She was, typically enough, eating: she was advertising a new kind of chocolate cake, and the picture showed her in a shining kitchen gazing in rapture at this cake, then cutting a slice and raising it to her moist, curved, delightful lips. There the picture ended. It would not have done to show the public the crumbs and the chewing. I was very excited by this fleeting glimpse, as I always am by the news of old friends, and it aroused in me a whole flood of recollections, recollections of Sophy herself, and of all that strange season, that Garrick year, as I shall always think of it, which proved to me to be such a turning point, though from what to what I would hardly like to say.

Poor old Sophy, I allowed myself to say, thinking that she would not much like being on a cake advertisement; and then I remembered the last time I had said Poor old Sophy, and that in any case, she would have earned a lot of money from that tantalizing moment. There is perhaps something finally unpitiable in Sophy, just as there is in me. We are both in our ways excellent examples of resilience, though I seem obliged to pass through many degrees of meanness on my way, whereas she just smiles and wriggles and exclaims and with a little charming confusion gets by. I like Sophy. I cannot help liking Sophy. And if there is a defensive note to be detected in that assertion, I am not in the least surprised.

That chocolate cake vision made me think back, as I said, over the whole lot, right back to the very beginning, to the occasion when I first realized that David was really intending to go to Hereford. I had just finished putting Flora to bed, and I came downstairs, splashed and bedraggled from her bath, to find David nursing the new baby and drinking a glass of beer. He had poured some stout for me, which was the only thing he would let me drink. When I appeared he handed the baby over quickly, and as I sat down and prepared to feed him, wondering if I would ever get him to wake at a less exhausting time, Dave spoke.”

Margaret Drabble (Sheffield, 5 juni 1939)

Zie voor nog meer schrijvers van de 5e juni ook mijn blog van 5 juni 2017 deel 1 en eveneens deel 2.

05-06-2019 om 18:19

geschreven door Romenu

Tags:Federico García Lorca, Adriaan Morriën, Ken Follett, Paul Farley, Geoff Dyer, Margo Lanagan, Carel Peeters, Robert Franquinet, Margaret Drabble, Romenu

|